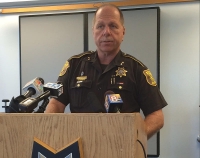

Cumberland County Sheriff Kevin Joyce runs a jail. But in a recent Portland Press Herald op-ed, Joyce writes that too many people are behind bars. And many of them, he says, are the wrong people.

GRATZ: Sheriff Joyce joins me now. Welcome.

SHERIFF JOYCE: Thank you for having me.

First let’s establish your credentials. How long have you been with the Sheriff’s Department?

I’ve been with the Sheriff’s Office for 32 years, and sheriff for eight.

Who are the people who wind up in jails or prisons that don’t need to be there?

A lot of people that have some sort of a mental illness or a substance use disorder that, you know, they’ve gone out and they’ve committed a crime. They did get arrested legally, and then they end up getting taken to jail. Some are destitute. They can’t even afford the bail, so they sit there until their court date or until a judge releases them. Others, they just get caught up in what I call the snowball effect, where, you know, they make a mistake, they commit a crime, and then it just keeps getting bigger and bigger and bigger and they get lost in the system.

What are some of the other consequences for jailing folks like this?

The public perception is that we’re doing drug rehabilitation in the jail. The reality is we’re not. So those folks could better be served by being at a drug rehabilitation program or getting some assistance – with medical assistance, with mental health, or substance use. To have the facade that, you know, we put them behind the walls of the jail and they’re off the street, they’re out of people’s hair, and, oh by the way, we’re fixing them – when we’re not. It’s just a false sense of security, in my mind.

Well, you know, it occurs to me one of the things that makes sentencing reform difficult is fear. You mentioned just a moment ago that people, once they’re in jail, they’re off the streets. And folks will naturally presume they’re off the streets, they’re not going to cause any more trouble. How do you kind of get past that?

The first thing is the short-term gratification. You know, if somebody is arrested and picked up and taken off the street and put in jail, they’re going to get back out. And if we haven’t done anything to find the root cause and to fix the root cause, then that individual, or those individuals, are going to go back to what they know best. And if people are all set with using the jail that way, then they have to be able to pay for it. And nobody wants to pay for the jails. So I think we’ve got to start looking for root causes. You know, I’m often saying that the people who are peddling this poison, this opiates, they belong in jail. We’ve got plenty of beds for those folks. For the person that gets caught the first time with a little bit of an amount – yes, that’s technically illegal. But they’re doing it because their brain has been rewired, their body is craving the drug, and they are going from point A to point B to utilize this drug. And I believe that rather than locking them up and just pushing the can down the road we ought to have some sort of a diversion where we can probably take care of the root cause.

You talk about the bill that comes due from the jail. Obviously, whether it’s substance abuse treatment or mental health treatment, those things have a cost as well. Is it less expensive to deal with them in a non-jail setting? Or is it potentially less expensive to deal with them in a jail setting?

In some cases, it could be less. I was speaking with a nurse that was doing their master’s degree thesis on the fact of whether or not it was cheaper to send somebody to a drug rehabilitation versus jail. It was cheaper. So if it’s cheaper, that’s a good business decision. And if they are fixing the person, or fixing the person’s needs, then that’s a good business decision as well. If in other cases it’s more expensive – even by a little but you’re fixing the problem – then I would say that’s money well spent too.

Now you did write about some of the sentencing reforms Maine made.

Yes.

Tell us a little bit about them.

The big one was in 2016 – they took possession of opiates from a felony down to a misdemeanor. Like I said, this is not the repeat offender. This is not the drug dealer. This is the person that’s using it. Keeping in mind this is a disease, we don’t lock people up because they have a high blood pressure. We try to fix that problem. We don’t lock people up because they have diabetes. We try to fix that problem. You know, some individuals that have the opiate addiction – they have it because they had surgery and they took their medications as prescribed and they kept following it and they became addicted and they didn’t know it. And now it’s not them making the decision. It’s their brain and their body craving it.

So what are the further reforms you’d like to see the state do?

I don’t have anything specific. It’s not going to be something that one law is going to strike down. It’s really getting the players all in one room and saying: ‘Is there a better way to build a mousetrap?’ Because the one we have now may have been efficient 20 years ago but it’s outdated now.

Sheriff, thank you very much for the time. We appreciate it.

Thanks for having me on.

Leave A Comment