Some west side of Augusta residents are seeking to limit what they say is an increasing number of group homes moving into their neighborhoods.

AUGUSTA — A proposal to ban any new residences from a large section of Western Avenue — aimed, in part, at stopping the increasing number of group homes locating there — has been rejected by city councilors.

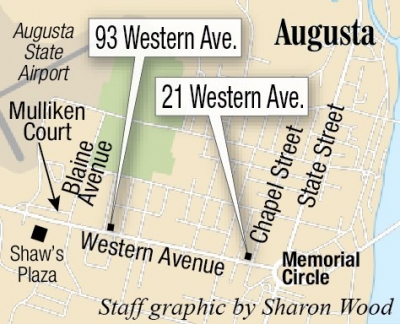

Ward 1 Councilor Linda Conti sponsored a proposal to put a moratorium in place for any new residential development on a section of Western Avenue, roughly between Memorial Circle and Mulliken Court and Blaine Avenue. She also proposed asking the Planning Board to consider whether residential development should be banned there permanently.

In the proposal to ban that development on the busy four-lane road, it was noted that potion of Western Avenue is nearly all commercially developed and only has a few residential properties. It also stated the intensive commercial use in that area made it incompatible with residential development.

But, while Conti said the highly commercial nature of Western Avenue may make it an undesirable place to live, she acknowledged the intent of the proposal was also to prevent what she said has been an increasing number of group homes on the west side. That includes two new homes — at 21 and 93 Western Ave. — that will serve as drug addiction recovery houses, providing housing and treatment to former Kennebec County jail inmates as part of its new medication assisted addiction treatment program.

Conti said concern over that issue, and the recovery houses and associated drug treatment programs, prompted numerous west side neighborhood residents to decry the changes in their neighborhood. They asked for councilors’ help at a heavily-attended council meeting June 13.

“One of the problems is we cannot regulate or limit in any way the number of group homes and, you know, residential housing, once it is allowed, all types of residential housing is allowed,” Conti said at a June 27 council meeting. “And we’re trying to not become the city that has group homes and living arrangements like that all up and down Western Avenue.”

Ward 3 Councilor Harold Elliott, at the June 27 meeting at which the proposal was rejected, said he believes what was behind the proposal was not concern for residents who might live on Western Avenue amid commercial development but, rather, at attempt to prevent recovery houses and other group homes from locating there.

“I know what the intention is, but it does not mention it in this paragraph,” Elliott said of the proposal’s wording that mentioned only that commercial use was the main use of Western Avenue and it may thus be incompatible with homes and apartments. “This is going about it in a roundabout way.Timothy Cheney, owner of ENSO Recovery, talks during a news conference May 2 at Capital Judicial Center in Augusta. Kennebec Journal photo by Joe Phelan

Timothy Cheney is owner of ENSO Recovery, the developer of the two recovery houses and organization overseeing the county jail’s recently started medication assisted addiction treatment program which began recently at the county jail. He acknowledged that the recovery houses have drawn fierce opposition from some of their neighbors.

Cheney said residents’ fears are misplaced, as former inmates participating in the program and living in the homes will be closely monitored — including being drug tested — and are trying to improve their lives by overcoming their addictions. He said studies indicate when a recovery house moves into a community, illegal drug use declines in that community.

“People are dying every day,” Cheney said Tuesday. “Recovery houses are a proven, established part of sustained recovery, nationwide. And housing is a critical component of that. You don’t sustain your recovery if you’re living under a bridge, or you return to the environment in which you were using drugs.

“People need to understand this is a community problem and a healthcare issue, not a criminal issue, not a moral issue. People in recovery have to live somewhere,” he added. “Nobody asks to be an addict. They have an illness. At least, in a recovery home, they’re being monitored, and they’re drug and alcohol free.”

At the June 13 meeting, Conti said her neighbors are concerned about neighborhood changes, including what she said is a plethora of medication assisted treatment programs where Suboxone is prescribed, such as with the ENSO Recovery one.

She agreed that Suboxone is “the gold standard” medication for helping people escape drug addiction, but that one part of Augusta shouldn’t be home to such a disproportionate number of treatment operations, since drug addiction is a problem everywhere, not just Augusta. Conti said Suboxone should be prescribed, like other medications, by primary care doctors, but that doctors “don’t want these people lined up outside their offices.”

“It’s not that we don’t want to be part of the solution, we just want it to be done in a planful way and not an ad hoc haphazard way so we end up with our neighborhood primarily composed of that kind of use,” Conti said. “There will always be stigmatizing around this disease, as long as it is treated in this way and not integrated into the established medical system. People are going to say I’m against substance abuse treatment, that I’m stigmatizing people, but in truth what’s stigmatizing people is the way this product is delivered.”

Several west side residents spoke out against the recovery houses encroaching on their neighbors at the June 13 meeting.

“I’m very familiar with criminals and their mindset,” said Sarosh Sher, an Air Force combat veteran who moved to Lincoln Street with his wife and two kids in 2015. “Nobody can sit here and tell me that facility is safe. That my children will be safe, or the people in my community will be safe. Nobody is going to tell me there will be no overdoses. My daughter should not have to worry about seeing a potential overdose when she’s riding her bike after school. She’s 10 years old.”

Group homes, under state housing regulations, are generally allowed wherever single family houses are allowed.

Cheney said ENSO’s recovery homes in Augusta will likely be occupied in about three weeks.

Last week, councilors voted down the proposed Western Avenue residential development ban, 5-2, with only Conti and At-Large Councilor Marci Alexander voting for it.

“I can’t conceive of any circumstances in the world where I would want to eliminate the possibility of residential use along Western Avenue,” said At-Large Councilor Mark O’Brien.

Last week, however, councilors did approve a 90-day moratorium, in a 4-3 vote, on commercial development in a zoning district encompassing much of Winthrop Street. They also agreed to ask the Planning Board for a recommendation on Conti’s proposal to permanently ban all new non-residential development in that zoning district.

Conti said neighbors are concerned about commercial development increasingly encroaching on their homes, and bringing unwanted foot and vehicular traffic to the neighborhood.

Numerous neighborhood residents cited those types of concerns when they spoke out against a currently dormant controversial proposal to open a mental health and substance abuse counseling service at 103 Winthrop St.

“People are dying every day,”

This photo, taken on Wednesday, shows 93 Western Ave. in Augusta. Kennebec Journal photo by Joe Phelan

This photo, taken on Wednesday, shows 21 Western Ave. in Augusta. Kennebec Journal photo by Joe Phelan

Leave A Comment